“The Quarry Collective” is an architectural study delving into the architecture accompanying rehabilitation. The project operates at the intersection between architecture, ecological and social studies, stating the interdisciplinary future of the architectural profession.

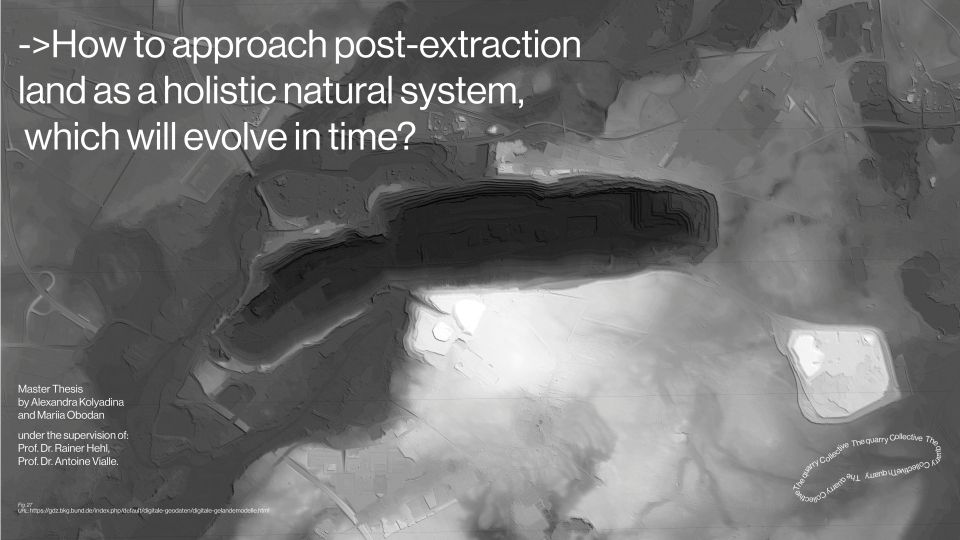

The Rüdersdorf limestone quarry, situated 30 kilometers eastbound from Berlin, stands as a testament to centuries of industrial activity. This vast landscape, with the hustle of extraction gradually declining, now seemingly lies in wait, marked by the scars of its past but rich with the promise of renewal.

Scars and scales

Limestone extraction at Rüdersdorf has profoundly disrupted natural cycles that have evolved over millions of years. One piece of the quarried stone takes us back 250 million years, to a time when the area was an ocean basin, its depths accumulating layers of microorganisms that would eventually become limestone. The challenge now is to navigate the vast temporal scales of natural processes needed to restore the balance disrupted by industrial activity.

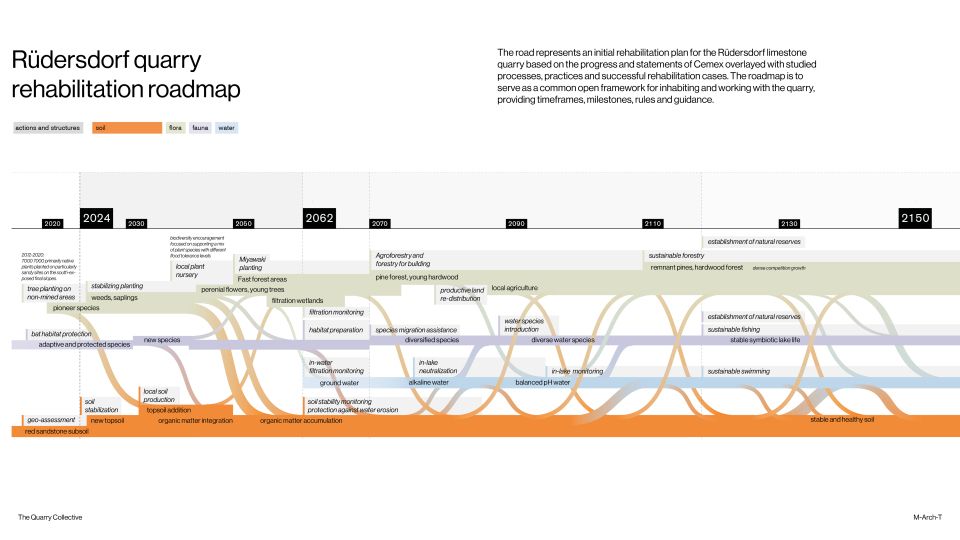

Modern industrial landscapes often suffer from a short-sighted approach, leaving behind barren expanses once resources are exhausted. The Rüdersdorf quarry, operated by CEMEX, will cease operations in 2062, necessitating a comprehensive rehabilitation plan. The costly and complex rehabilitation of Lusatia's coal mines of Brandenburg serves as a cautionary tale, underscoring the necessity of integrating rehabilitation efforts from the very beginning of mining operations. The LMBV company responsible for the Lusatia’s case concluded that starting rehabilitation early is crucial to mitigate complexity and cost.

Generational care and unpredictable future

To approach the notion of non-human time scales, we turn to the concept of collective management. In the midst of the Swiss Alps, the Oberallmeinkorporation has sustainably managed local resources for over 900 years, demonstrating the effectiveness of long-term, community-driven stewardship. Applied to Rüdersdorf, such stewardship could ensure that rehabilitation efforts are sustained over the long term.

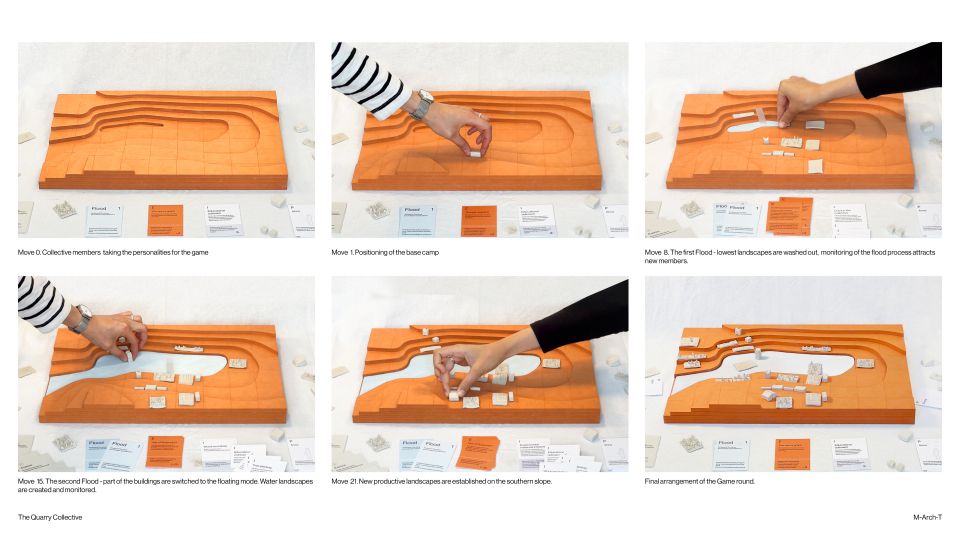

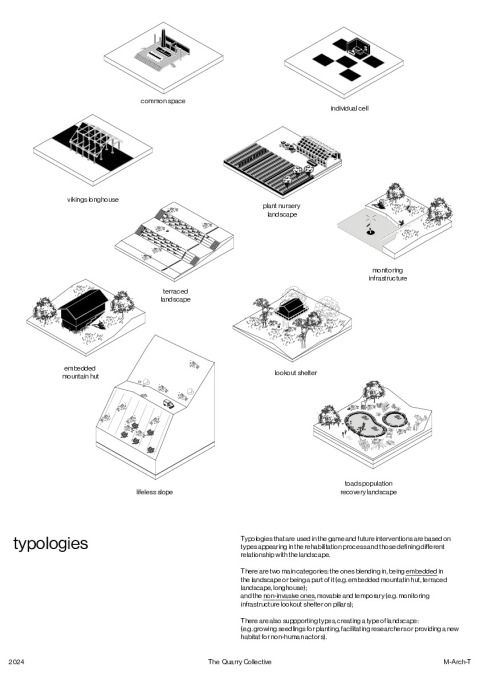

To address the unpredictability of the future, we developed a board game within our project. This game serves as a model for negotiation and learning in the context of rehabilitation. By simulating various scenarios repeatedly, it provides tangible insights into the potential outcomes of different collective dynamics and external ecological factors. The internal impulses of collective development, combined with external ecosystem events, shape the spaces that host our collective, fostering adaptable and responsive architectural interventions.

Architecture of rehabilitation

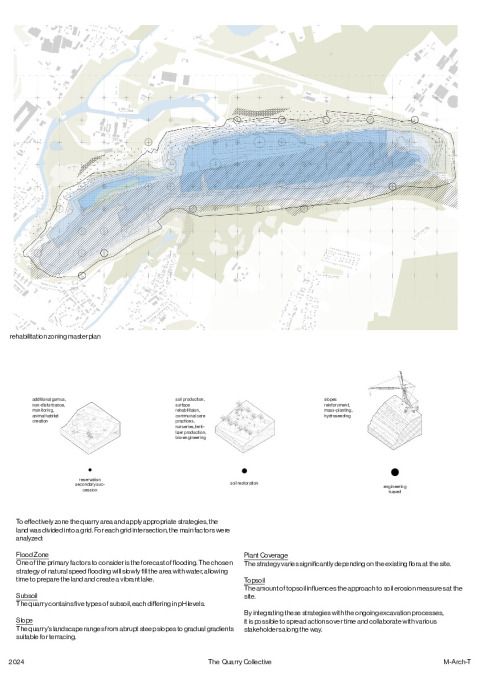

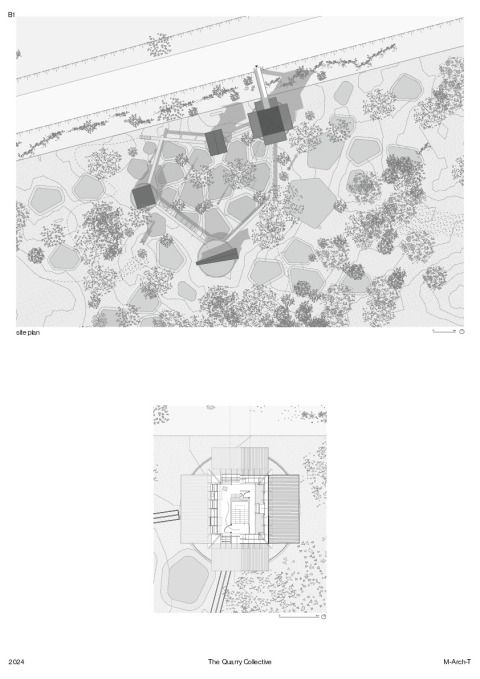

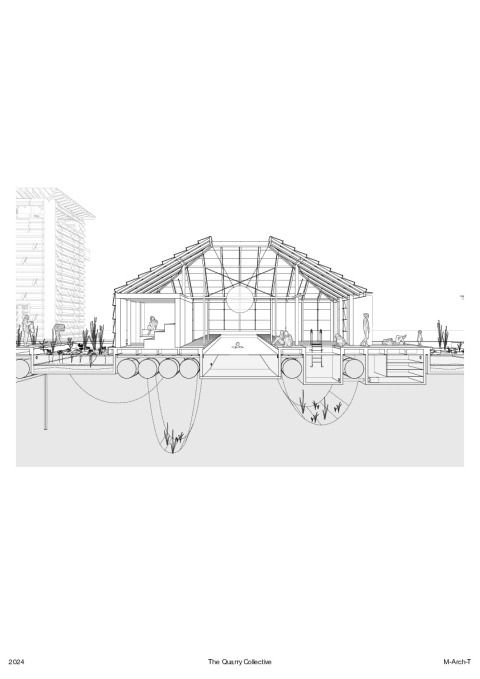

In the span of the proposed 150-year rehabilitation roadmap for Rüdersdorf, we envision several adaptive interventions: embedded for the zone not affected by the future flooding, and non-invasive for the affected zone.

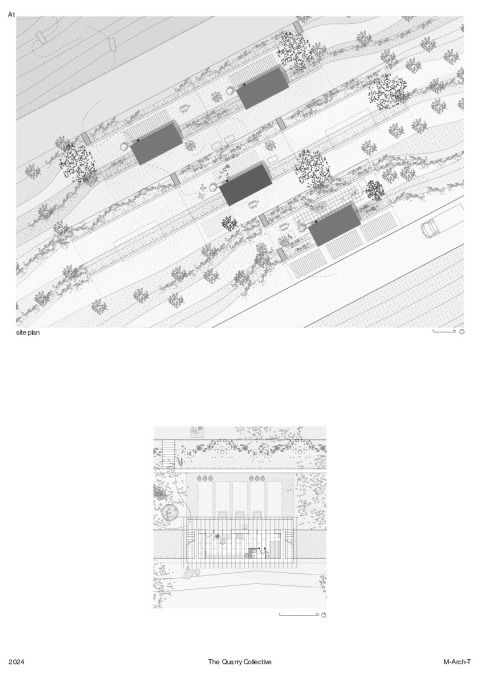

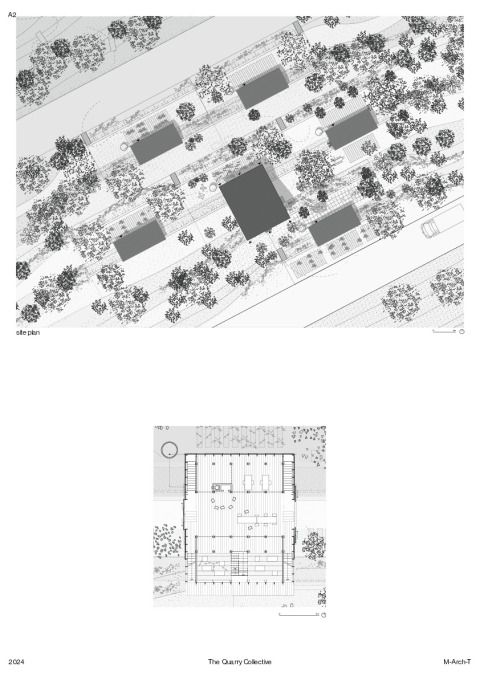

The initial stage focuses on soil and plant experiments. Geologists, soil scientists, and enthusiasts will transform the southern quarry slope, embedding their working-living quarters into the landscape to prevent erosion while cultivating new soil and plant life.

As the collective grows, the focus shifts to knowledge sharing and community building. Educational programs will be established in the expanded camp building to foster a deeper connection to the land and ensure the continuity of rehabilitation efforts across generations.

In the most challenging environments of the formed biotopes going through slow-paced flooding, non-invasive and dismantlable huts and pavilions will protect emerging ecosystems, allowing for human care without disrupting natural processes.

The final phase centers around water, transforming the quarry into a water-centric habitat. As the quarry floods, floating retreats will be introduced, promoting water care and habitat creation. These retreats will serve as educational and recreational spaces, encouraging visitors to engage with the landscape as caretakers rather than mere users.

Successful rehabilitation is not just a technical challenge but a social one, requiring deep engagement and long-term stewardship. Through the mindful consideration of time, we aim to create landscapes that reflect the enduring bond between humanity and the earth, demonstrating that effective rehabilitation requires a commitment to continuous stewardship, adaptability, and the integration of human and natural processes over the long term.

The Rüdersdorf limestone quarry, situated 30 kilometers eastbound from Berlin, stands as a testament to centuries of industrial activity. This vast landscape, with the hustle of extraction gradually declining, now seemingly lies in wait, marked by the scars of its past but rich with the promise of renewal.

Scars and scales

Limestone extraction at Rüdersdorf has profoundly disrupted natural cycles that have evolved over millions of years. One piece of the quarried stone takes us back 250 million years, to a time when the area was an ocean basin, its depths accumulating layers of microorganisms that would eventually become limestone. The challenge now is to navigate the vast temporal scales of natural processes needed to restore the balance disrupted by industrial activity.

Modern industrial landscapes often suffer from a short-sighted approach, leaving behind barren expanses once resources are exhausted. The Rüdersdorf quarry, operated by CEMEX, will cease operations in 2062, necessitating a comprehensive rehabilitation plan. The costly and complex rehabilitation of Lusatia's coal mines of Brandenburg serves as a cautionary tale, underscoring the necessity of integrating rehabilitation efforts from the very beginning of mining operations. The LMBV company responsible for the Lusatia’s case concluded that starting rehabilitation early is crucial to mitigate complexity and cost.

Generational care and unpredictable future

To approach the notion of non-human time scales, we turn to the concept of collective management. In the midst of the Swiss Alps, the Oberallmeinkorporation has sustainably managed local resources for over 900 years, demonstrating the effectiveness of long-term, community-driven stewardship. Applied to Rüdersdorf, such stewardship could ensure that rehabilitation efforts are sustained over the long term.

To address the unpredictability of the future, we developed a board game within our project. This game serves as a model for negotiation and learning in the context of rehabilitation. By simulating various scenarios repeatedly, it provides tangible insights into the potential outcomes of different collective dynamics and external ecological factors. The internal impulses of collective development, combined with external ecosystem events, shape the spaces that host our collective, fostering adaptable and responsive architectural interventions.

Architecture of rehabilitation

In the span of the proposed 150-year rehabilitation roadmap for Rüdersdorf, we envision several adaptive interventions: embedded for the zone not affected by the future flooding, and non-invasive for the affected zone.

The initial stage focuses on soil and plant experiments. Geologists, soil scientists, and enthusiasts will transform the southern quarry slope, embedding their working-living quarters into the landscape to prevent erosion while cultivating new soil and plant life.

As the collective grows, the focus shifts to knowledge sharing and community building. Educational programs will be established in the expanded camp building to foster a deeper connection to the land and ensure the continuity of rehabilitation efforts across generations.

In the most challenging environments of the formed biotopes going through slow-paced flooding, non-invasive and dismantlable huts and pavilions will protect emerging ecosystems, allowing for human care without disrupting natural processes.

The final phase centers around water, transforming the quarry into a water-centric habitat. As the quarry floods, floating retreats will be introduced, promoting water care and habitat creation. These retreats will serve as educational and recreational spaces, encouraging visitors to engage with the landscape as caretakers rather than mere users.

Successful rehabilitation is not just a technical challenge but a social one, requiring deep engagement and long-term stewardship. Through the mindful consideration of time, we aim to create landscapes that reflect the enduring bond between humanity and the earth, demonstrating that effective rehabilitation requires a commitment to continuous stewardship, adaptability, and the integration of human and natural processes over the long term.